Over the last few years of working with data I’ve collected a toolbox of essential tools that I think all Data Scientists should know and use. All of these tools will not only help you be more efficient as a data scientist or data analyst, but will also help you work better within a team, be more organized and flexible and produce analyses that will be more easily reproducible by others.

These probably aren’t the only tools you’ll end up needing to use day-to-day, but this list of tools will be universally useful.

So without further ado, here is my list of essentials:

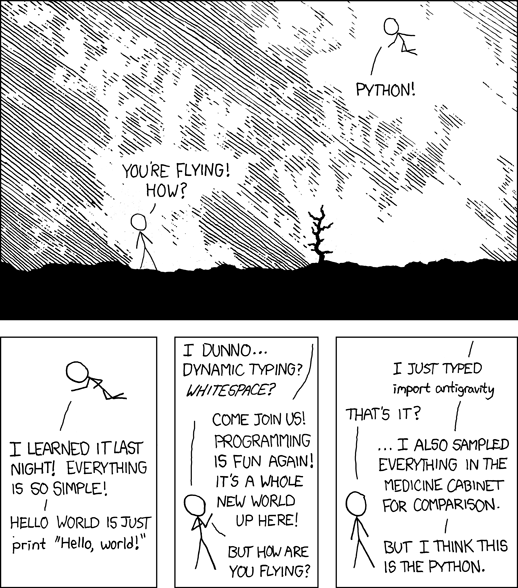

Python

To start out with, I have to mention that I’m totally biased here. I really love Python and it’s my go-to language of choice when it comes to almost any programming task.

The R vs Python (vs Matlab and many others) language wars in data science have been around for a long time, and many have chimed in on it. I’m not here today to convince you which language is better for data science, or even that you have to choose (I’m a big fan of R too, and even though Python is catching up, R has been a de-facto standard for a long time).

But when it comes to a general scripting language, Python is really hard to beat. It’s easy to learn, easy to read and write and comes with a vast amount of packages that be used for general purpose automation and data munging.

Python is perfect for consuming web API’s or scraping data from websites. It’s great for working with various data formats such as json, csv, excel, or something more exotic like Parquet, Avro or Protobuf. It’s also really great for connecting to external databases like Postgres, Redshift or MongoDB.

These are just a few reasons to know and love this lovely little scripting language and I could probably rant on for much longer, but I’ll leave this here for now.

If you wanted to learn Python in a hurry, I would suggests this tutorial by learnxinyminutes or if you wanted a more thorough treatment of the subject try Learn Python the Hard Way

Docker

To say that Docker has changed the way I think about Data Science is an understatement. Probably the first thing I’d do when starting a new data analysis is to set up my containerized environment.

If you’re unfamiliar with Docker, it’s basically lets you run an application within a container, which is like a light-weight virtual machine that can run completely isolated from it’s host environment and which creation can be automated in a way that you can always recreate it from scratch.

Containers are created from images, which can be thought of complete snapshots of an environment at any point of time. Images can be shared with other people and extended, and if you share your analysis code along with the Docker image that was used to create it initially, you can pretty much guarantee that your analysis will be reproducible.

This makes reproducible analysis really easy, and it makes it really easy for someone to take any analysis you did and run it for themselves without having to install any software (other than Docker).

A good place to get started with Docker would be this awesome tutorial.

Bash

The Unix OS was invented in the 1970’s and to this day it’s many variants and offshoots, like Linux and Mac OSX are still widely in use and beloved by software engineers and data scientists.

Learning to use to use the bash shell and working on the command-line is an essential data science skill that unlocks a world of computing tools that have been developed over decades (some of which I’ll cover later on in this post) and will not just help you become a more efficient data scientist, but a more efficient computer user in general.

Learning the basics of using the terminal will also enable you work on computers with no graphical user interface, like a beefy EC2 server your running in the cloud.

In my opinion, the greatest benefit to learning bash is it’s philosophy of using simple, small, modular tools that can be composed together in pipelines to produce solutions to complex problems.

If you want to get started with bash quickly this is a great guide. For a more data science slant, Data Science at the Command Line is a great read.

Git and Github

Ever find yourself wishing you could go back in time and see what you or a team mate did the day before, or week before? Ever made a change to code that you wish you could revert later? Ever find yourself making backup folders before making changes, or sending source code or data to other people using email or Dropbox? If so, you need look into version control control system.

Probably the best and most widely is VCS software in existence is git. Github ( and Gitlab) has also become a widely used platform for hosting git repositories and managing open source or private projects.

Git is a distributed version control system, meaning that you don’t need a central server running somewhere to orchestrate versioning and change management. Projects are organized around repositories and each collaborator can work on a separate copy of the repository (and it’s history). Changes to repositories (or repos for short), are made through commits, and each commit is recorded in the history of the repo.

Experimental changes can be done in separate branches, that can be peeled off from the main master branch and later be merged back.

Github is a platform that allow you to host git repositories and collaborate with others on projects. It has become the de-facto standard for hosting open source projects, and adds the ability to easily fork other people’s repositories send Pull Requests, ie commits you’ve made to your own fork that you want to have merged back in to the original repository.

If you wanted to get started with git and Github, this tutorial will teach you the basics quickly, while this is a great, more in depth guide.

Make

GNU make is a simple, yet surprisingly powerful command-line tool that let’s you automate tasks and specify the dependancies between them, by creating ‘recipes’ that can be executed to run a sequence of steps that will create a final output.

Make uses simple file called Makefile that let’s you define so called targets (task outputs) and a dependency tree (or more technically, a directed acyclic graph of dependancies) of input files and commands that can be used to construct the targets. The power comes from being able to express the dependancies in a simple, declarative language, which make then uses to figure out the exact sequence of steps needed to run whenever anything changes.

Make is also language-agnostic, anything you can do on the command line can be automated and it comes standard with almost any unix or linux system.

If you wanted to get started with Make, especially for data science, this is a great place to start.

SQL

SQL has been around for a very long time, and it’s arguably still very much the lingua-franca when it comes to extracting, searching and transforming data. A lot of web applications use SQL as it’s transactional database. Many large statistical data collection projects will store data in a SQL database as well.

As a data scientist, you might be using not only traditional, transactional SQL databases such PostgreSQL, MySQL or SQLite, but over the last few years many analytics-focused’ databases have emerged, such as Amazon Redshift, Google BigQuery or Snowflake.

Many Big Data platforms also offer a higher level SQL interface, such as Apache Spark with SparkSQL, Pig and Hive on Hadoop, Presto, Amazon Athena, etc.

Learning SQL is one skill that you could probably transfer to many roles throughout your career, and will unlock a wealth of data.

Markdown

Being a data scientist doesn’t mean just discovering insights from data, but also communicating your results to peers and colleagues. This often means not just keeping track of what data you use and which methods you used to analyse the data, but also capturing and documenting what you learn. Markdown is a simple, but surprisingly flexible and useful way of producing documentation and presenting it to others. It’s an easy to learn, very readable and widely supported markup language that mostly stays out of your way and just let’s you do the job quickly and effortlessly.

Since it’s all text it’s easy to use anywhere, without having to deal with heavyweight binary formats. Markdown documents can also easily be extended to do anything almost you can do in a webpage, by using inline HTML.

The best part of Markdown is that’s it’s concise, easy to read and write, and easy to learn. You can basically learn all of it in an hour or so, here is a great place to start.

An example

The best thing about this list of tools is how well they work together. The easiest way to illustrate this is with an example project.

I created a toy analysis to show how you could go about using most of the tools I’ve listed in this blog post. You can check it out over here.

To get a better idea of how it all fits together, you can start with the README markdown file.

You’ll see that I make heavy use of Make to automate the analysis and set up dependencies.

The Makefiles in turn lean on bash to do some inline data collection and data processing, but I also make use of Python (and Pandas) to some of the more involved data processing.

The Python code together with the main analysis Notebook runs within a Docker container.

Finally, I can use git and github to share my analysis and anyone can step through my commit history to see how the project was put together.

Now over to you!

And that concludes my super opinionated list of essential data science tools. This is by no means an exhaustive list of tools that you’ll find useful for doing data science, and might be quite different from your own list, but over time these tools have served me very well. My hope is that perhaps a couple of these suggestions might serve you well too.

Where do you agree or disagree with me? What tools are on your essentials list? I would love to know!